The historical background of written transmission

The repertoire of the so-called Gregorian chant is based on a Roman sacramentary called “Hadrianum”, because Charlemagne asked Pope Hadrian I for a sacramentary to establish the Roman rite in the Frankish Empire arguing in front of Frankish cantores that his father Pippin III already tried to romanise the liturgy of the Empire (Admonitio generalis, 23 March 789, source: CH-SGs 733, pp. 15-64, edition: dMGH). Here an extract (CH-SGs 733, pp. 56f, dMGH, p. 61):

Omni clero. Ut cantum Romanum pleniter discant, et ordinabiliter per nocturnale vel gradale officium peragatur, secundum quod beatae memoriae genitor noster Pippinus rex decertavit ut fieret, quando Gallicanum tulit ob unanimitatem apostolicae sedis et sanctae Dei aeclesiae pacificam concordiam.

To all clergy. That they fully learn Roman chant and correctly celebrate the night and day offices, as our father of blessed memory, King Pippin, decreed when he abandoned the Gallican [chant] for the sake of unity with the Apostolic chair and pacific concord within the holy church of God.

Charlemagne obviously referred to an exchange with Frankish cantors at Rouen, who learned from the Primicerius Symeon, one of the directors of the Roman Schola cantorum. We know about this meeting, because Pope Paul I (757-767) wrote a letter to Pippin, in which he excused the abrupt end of the workshop caused by the sudden death of the first director Georgius (dMGH):

In eis [litteris vestris] siquidem conperimus exaratum, quod presentes Deo amabilis Remedii germani vestri monachos Symeoni scole cantorum priori contradere deberemus ad instruendum eos psalmodii modulationem, quam ab eo adprehendere tempore, quo illic in vestris regiminibus extitit, nequiverunt; pro quo valde ipsum vestrum asseritis germanum tristem effectum, in eo quod non eius perfecte instruisset monachos. Et quidem, benignissime rex, satisfacimus christianitatem tuam, quod, nisi Georgius, qui eidem scolae praefuit, de hac migrasset luce, nequaquam eundem Simeonem a vestri germani servitio abstolere niteremur ... Sed defuncto praelato Georgio et in eius isdem Symeon, utpote sequens illius, accedens locum, ideo pro doctrina scolae eum ad nos accersivimus. Nam absit a nobis, ut quippiam, quod vobis vestrisque fidelibus onerosum existit, pergamus quoquomodo; potius autem, ut praelatum est, in vestrae caritatis dilectione firmi permanentes, libentissimae, in quantum virtus subpetit, voluntati vestrae obtemperandum decertamus. Propter quod et praefatos vestri germani monachos saepe dicto contradimus Simeoni eosque obtine collocantes sollerti industria eandem psalmodii modulationem instrui praecepimus et crebro in eadem, donec perfectae eruditi efficiantur, pro amplissima vestrae excellentiae atque nobilissima germani vestri delectione, ecclaesiasticae doctrinae cantilena disposuimus efficaci cura permanendum

In your [letters] we find requested that certain monks of your brother Remedius, beloved of God, should be directed to Symeon, prior of the schola cantorum, for instruction in psalmic music; which they were unable to receive from him during his stay in your kingdom. You say your brother was saddened that his monks could not be perfectly instructed. And yet, gracious king, let us assure your Christian majesty that if George, who headed the schola [cantorum], had not died, we would not have withdrawn Symeon from your brother's service. But with George deceased and Symeon needed to take his place, as his natural successor, we recalled him to Rome for the instruction of the schola. Far be it from us to act in any way that would distress you and your followers. Rather, as we have said, remaining firm in our love for you, we most willingly strive, as we are able, to accommodate your wishes. Therefore we have assigned your brother's aforesaid monks to Symeon [at Rome] and installed them properly, and ordered that they be taught the music of psalmody, with frequent exercise, until they are perfectly instructed. For the ample delectation of Your Excellency and the noble enjoyment of your brother, we will have the ecclesiastical chants maintained with rigorous care.

Through the synode of Frankfurt 794 the Carolingian reform became official and the cantores had to abandon the former Gallican rite and to learn a vast chant repertoire provided in the sacramentary. The amount of mass chant was ten times larger in comparison with the repertoire sung during the Divine Liturgy in the Hagia Sophia of Constantinople (cathedral rite).

Transmission of chant, canonised scripture, and poetry were part of an art of memory and clerics regard themselves as the champions of this craftship. The sacramentary provided the text of Roman chant without using any musical notation than ekphonetic interpunction. The fact that a more detailed notation was used since the end of the 9th century is surprising, because it was neither used by Jewish cantors, neither by Sufi musicians, nor Hafizes during the following centuries. Some chronicles of the 9th century report that Frankish singers corrupted the Roman chant. In reaction Frankish cantors invented Western neume notation and used scripture to control the repertoire which was fashioned as "Gregorian chant", as a divine inspiration of Pope Gregory the Great expressed in an illumination of the Hartker Antiphonary:

Page 13 in the digital library of St. Gall

But Gregory lived 300 years before the neumes were invented as an evolution of the ekphonetic notation in the Frankish scriptoria, so he could not know the Saint Gall neumes written by the scriptores next to him. This hagiographic illumination transported a rather political message, because Gregory who was once a Roman diplomate in Constantinople, insisted on papal primacy against the patriarch of Constantinople, when he reorganised the devastated Rome as a Pope, while King Charlemagne usurped later the authority of the Byzantine Emperor, coronated as the Emperor of West and East Roman Empire by Pope Stephen II during Christmas 800.

The Roman tradition was still based on oral transmission, and it was not codified into notation before the end of the 11th century (the earliest chant book, the gradual and proser-sequentiary of Santa Cecilia di Trastevere, was written in 1071, CH-CObodmer 74, the gradual of the Schola cantorum dated some years later, I-Rvat Vat. lat. 5319). But the suspicions against the Frankish cantores during the 9th century are confirmed by these late chant manuscripts: the Roman-Frankish and the Roman or Old-Roman chant are based on the same liturgy, but they both offer a constantly different transmission of the same liturgical chant repertoire.

The function of 10th-century neumes

The oldest chant manuscripts fully provided with musical notation cannot be found before the 10th century, but there are manuscripts like Gradual-Sacramentaries with modal signatures which indicate the church tone, and they have even neume notation in smaller parts. One of the earliest examples is the Gradual-Antiphonary of Albi (Albi, Bibliothèque municipale, Ms. 44) which was written during the last decade of the 9th century. Folio 5 verso shows the beginning of the Christmas mass. The gradual "Viderunt omnes" was written by a scribe who left space for a notator. The notator just wrote some neumes over the beginning of the preceding introit, but did not continue his work. Nevertheless, these few neumes show remarkable details which are not known from contemporary paleo-Frankish notation. It is the oldest notation in a Southern French manuscript and it was called "proto Aquitanian". The notator used three different pedes. At the beginning (G—d) the punctum is replaced by a horizontal stroke (gravis) which indicate a quantitative accent on the first note. Later a liquiscent form (epiphonus) written over the syllable "et" is used. Over the syllable "natus est" the letter "b" substitutes a punctum. It indicates a b flat (b synnemenon), so the melody of these syllables might be reconstructed as ded c b flat.

Despite the fact that philologists are quite absorbed to reconstruct the diastematic (melodic) structure of the melos based on their knowledge of later notation, its early form makes evident that the melodic memory was not the main function of 10th-century neume notation. Obviously there was an oral practice for the pitches, as Notker of St. Gall described it by the use of troping melodies. This means that cantors recognised the melodies by melodic phrases, transcribed and grouped by neume notation. The neumes show clearly the number of pitches used in the melody, but they were memorised note be note by underlaid syllables. The early neumes, "adiastematic" or "in campo aperto", inform about the phrases of the chant, providing the melos note by note, but without exact information about the intervals—with the exception that some additional letters sometimes define, if the following note is continuing on the same pitch, above or below. Despite this imprecision concerning pitch, especially the notations developed in the scriptoria of Lorraine (Laon, Metz) and Switzerland (Sankt Gall, Einsiedeln) are very detailed in performance practice, while they are using numerous ornament signs, accents to express a certain rhythmic or agogic value of a note, and special signs (liquescentes) for the sound of semivowels, which also give some information about the local pronounciation of the Latin words. Even recent researches still continue to discover more and more details of this notation.

In comparison with Byzantine Round notation the characteristics of Western neume notation are: a detailed note by note transcription of the formulaic phrases and no modal keys which refer the mode of the melos. It is evident that the oral transmission of the melodic structure was so precise, that a later modal classification according to the eight mode system (oktōēchos) could be deduced by an analysis of an obviously unknown melos.

For this modal classification a certain manuscript type called tonary was used which is older than any fully notated chant manuscript: The earliest testimonies can be dated back some years before the Carolingian reform. In the later chant manuscript these tonaries often served as an appendix. A tonary refers each mode by a characteristic intonation formula and its psalmody, and usually the incipits of some antiphonal chants used as refrain between psalm recitation follow. In some rare cases cantores testified their classification of the chant by modal keys, later written on the margin, or the whole chant manscript provided each chant fully notated in the order of the eight modes.

The conclusions made by this method of modal classification are: The cantores adapted with the tonary each piece of chant according to the eight mode system which was not inherent in the whole repertoire. This way the notation and its (unwritten) transmission allowed a cantor to learn a huge repertoire of unknown chant without any knowledge of its melos and of the local school or tradition behind the melos. During the 10th century, the Roman chant tradition represented by the institution Schola cantorum was already a patchwork tradition which combined for an extravagant liturgy examples taken from different regional traditions of Western and Eastern plainchant. In contrary to Byzantine notation no signs like phthorai were used to indicate transpositions, so the new and very complex form of written transmission was based on a simplification of music theory and its main concern was a reliable and unambigious modal classification—a subject, which never interested a Greek psaltis. This simplification was due to the transfer that was offered to every cantor of the Frankish empire.

The evolution of Latin chant notation

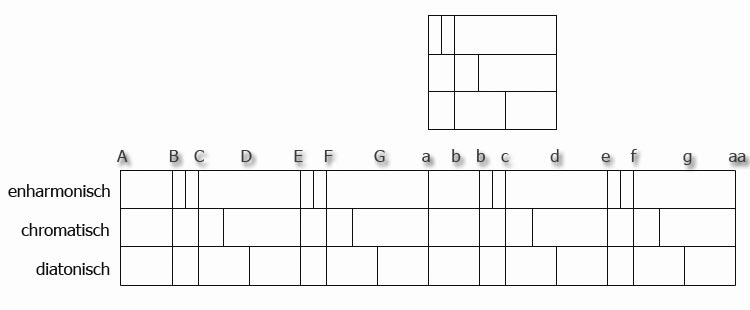

By the end of the 10th century the early notation became either unreadable after 120 years, or the huge repertoire of Roman-Frankish chant had to be taught in new founded monasteries like the ambitious reconstruction of Saint-Bénigne at Dijon or new foundations in Normandy. The oral note by note transmission was supported now by an additional letter notation (see the fully notated tonary for Saint-Bénigne de Dijon, F-MOf H159), an invention by William of Volpiano, a reform and founding abbot educated at Cluny Abbey. Its letters a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, k, l, m, and n (A—f) refer to the diatonic positions of the Boethian diagramm (including dieses: ⸡ to sharpen the half tone between E-F, ⸢ between a (h) and b flat (j) and ⸣ between b natural (i) and c (k)):

In a second step diastematic forms of notation had been developed soon, about 1010, in Aquitaine which tend to place a sign in a vertical position according to its pitch class (see the troper-proser with offertorial and tonary of Saint-Martial de Limoges, finished about 1025, F-Pn lat. 1121). One or more horizontal guide lines support the vertical orientation. The evolution towards staff, and square notation later in the late 12th century, was accompanied by a decline concerning all the details which were indicated by additional signs of the early neume notation of 10th century.

Details in performance of plainchant

The presentation here emphasises early chant notation and is focussed on an adequate performance of all the ornamental details and microtonal shifts, which are part of the modal practice and which were discovered during recent researches, when Western academic musicians became more familiar with the microcosmos of sound and pay more attention to medieval treatises whose authors sometimes tried to describe these details. Though we cannot be entirely sure about the exact meaning that some ornamental signs once had, this page does not only want to introduce into Western neumes, but also to encourage other musicians to cultivate their own understanding of these modal details of monodic chant.